Jenny Steele on Miami Beach, Morecambe and the revival of northern seaside towns

Jenny Steele. Courtesy of Shaw & Shaw

Jenny Steele is a Scottish visual artist based in Manchester, whose research-based practice most recently responds to mid-war modernist coastal architecture in North England, Scotland and Miami South Beach, through the processes of drawing, printmaking, textiles and sculpture.

For one of her most recent exhibitions, This Building for Hope, which took place at Morecambe's seafront Midland Hotel, Jenny undertook a research visit to Miami South Beach, and also looked into The Midland's architectural history at the RIBA and V&A archives in order to produce creative interpretations of her findings.

Following the success of her solo exhibition at Morecambe's iconic art deco hotel, we spoke to Jenny about this and more.

Tell us more about This Building for Hope

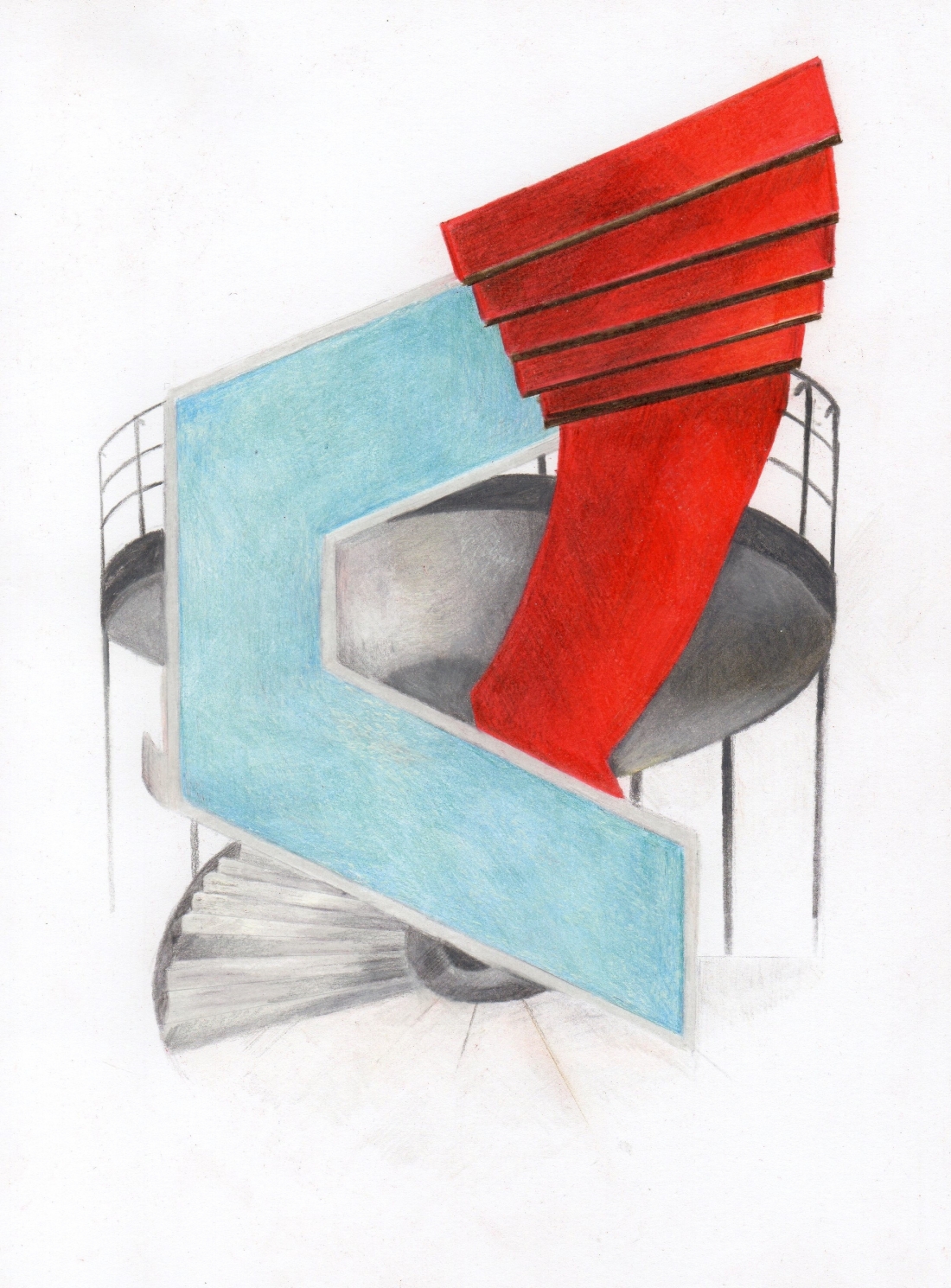

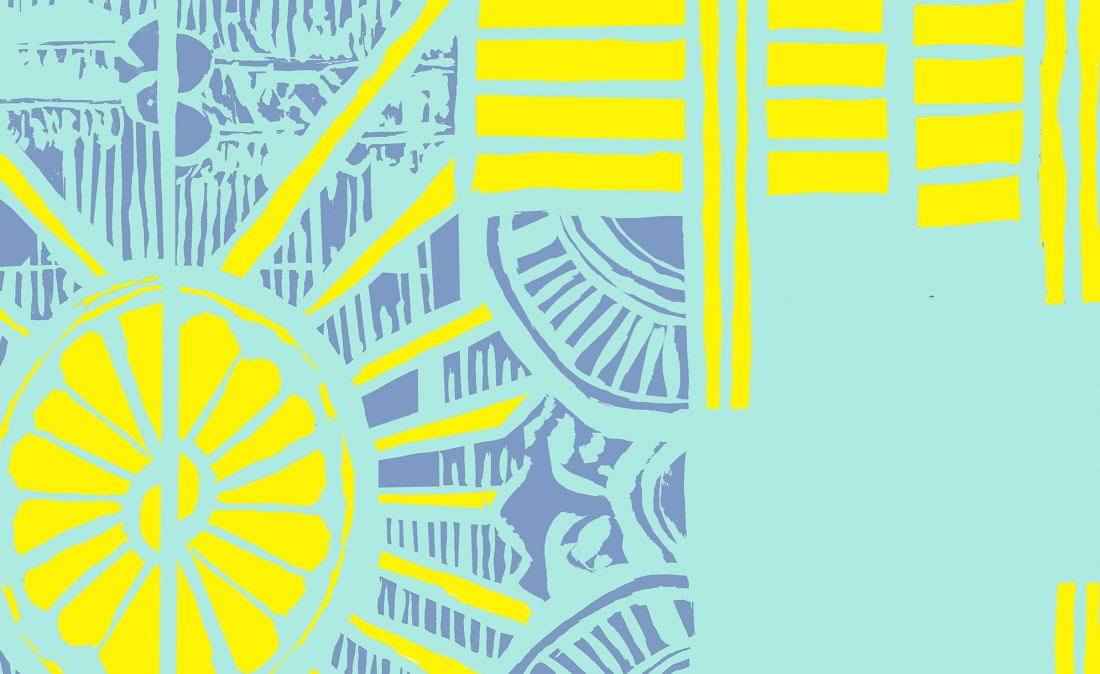

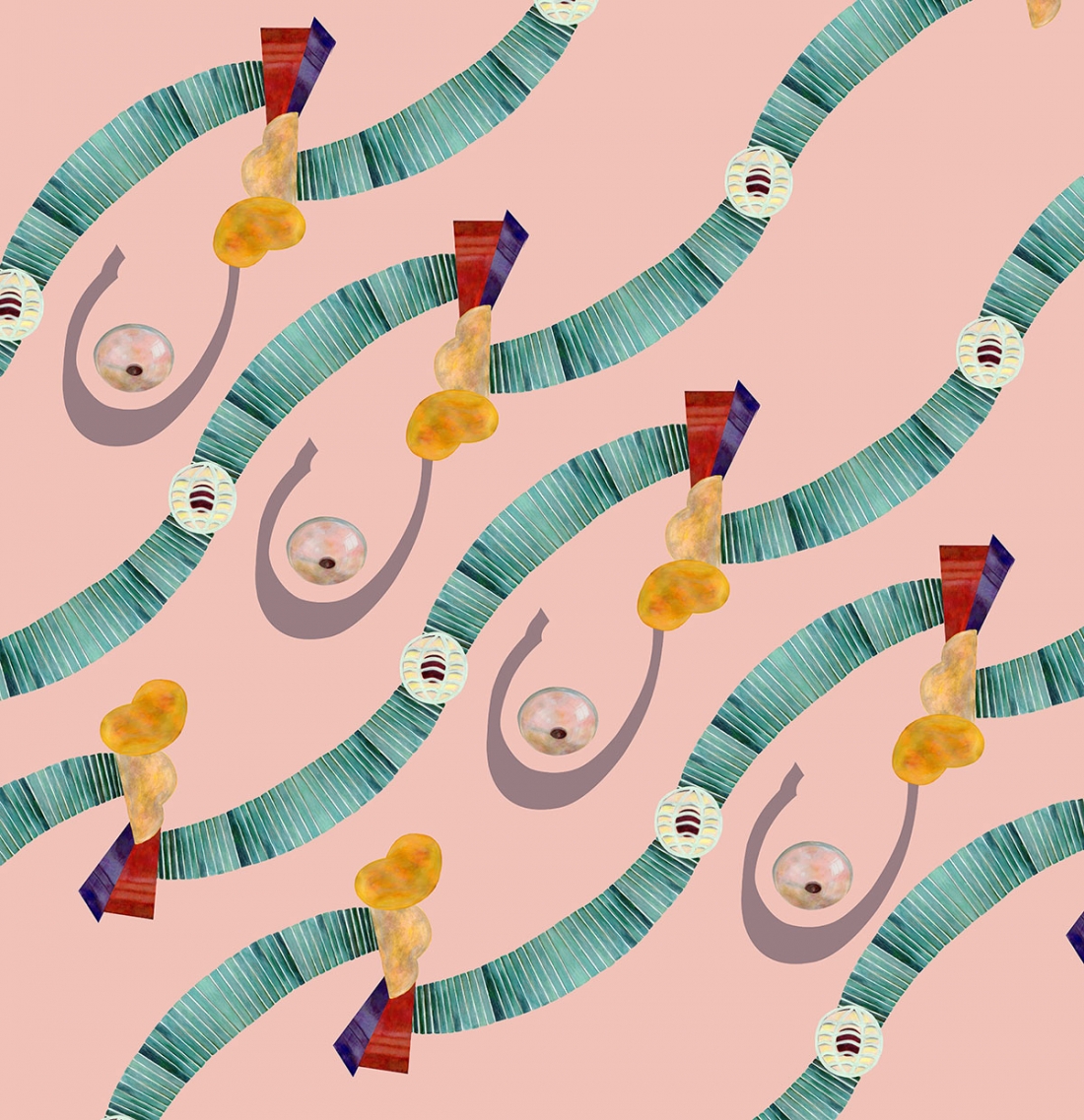

This Building for Hope was an exhibition of site-responsive work situated within the interior and exterior of the 1930s Midland Hotel, and along the Morecambe promenade. The work responds to my research into 1930s Seaside Moderne architecture in North West England and Scotland, in particular, The Midland, and a recent research visit to Miami Beach, to view Seaside Moderne architecture on Miami South Beach.

The work takes the form of sculpture and prints onto textiles and paper, a large window installation and a 56 metre long print along the curve of the promenade. The title refers to a local name for the building – when the hotel and tourism in the area fell into decline in the 1980s, local people looked to the large white building as ‘Morecambe’s White Hope’. They felt if they could find a way for the hotel to be renovated, it would turn around the fortunes of the resort.

What is it about Seaside Moderne architecture that sparks your interest so much?

I’m interested in many aspects of the architecture – from the reasons for its construction to the form of the design itself. Seaside Moderne architecture was built in the 1930s during the mid-war leisure boom when there was a social emphasis on wellbeing.

At this time everyone was allocated one weeks' holiday for the first time, therefore millions of people were travelling to the seaside, and new pleasure architecture, such as The Midland Hotel, Morecambe and The Blackpool Casino, Blackpool, was built to accommodate these people.

The design of this architecture commonly features interiors of light, air and openness – creating uplifting spaces, doubled with the relaxing and restorative seaside environment. The exterior of the buildings are consciously bold in their streamline design and sit confidently apart from other Victorian and Edwardian architecture on the coastline.

You recently visited Miami to help with your research. How was that?

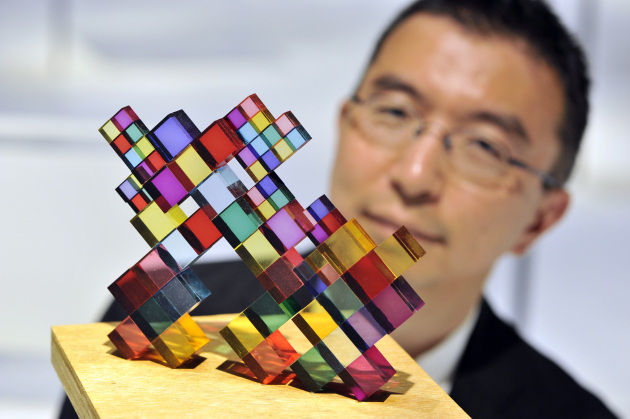

It was a fascinating experience to finally view examples first hand of Seaside Moderne architecture which I had read about so much. Miami South Beach has the largest preserved area of 1930s architecture internationally and is very different in some aspects to British examples.

The buildings are smaller, although there are hundreds of them all positioned together in one district, and have more decorative motifs on their exterior. During the 1980s, they were painted in tropical colours by the Miami Design Preservation League, who sought to reinvigorate and preserve the area, when it was threatened with demolition. Now it is an incredibly popular seaside resort, which was also helped by advertisement through TV and Film such as ‘Miami Vice’ and ‘Scarface’.

So the Midland Hotel in Morecambe plays a central role in this research. What is it about this place that you love so much?

The Midland was designed by architect Oliver Hill in 1933 and was commissioned by the London, Midland and Scottish Railway Company, who also built many other impressive hotels along their railway lines such as Gleneagles.

The hotel is quite unique in that, Oliver Hill, who was a relatively young architect at the time, oversaw all aspects of the design, down to details such as the crockery and linen. He commissioned three artists to make work for the interior, Eric Ravilious, Eric Gill and Marion Dorn, all of which apart from the Ravilious work is still in existence.

Within my research in the UK, The Midland had the most archival information available in the RIBA archive. I spent two days reading through letters between the financial controller of the hotel and Oliver Hill, and documentation relating to decision-making with each of the artists and suppliers. It was fascinating, and the language was like email exchange today.

How do you translate the style into surface patterns and designs? What’s the process?

I usually make a lot of drawings of features of the architecture's interior and exterior in paint or pencil. The overall form of the works is usually informed by a specific narrative or idea that has come up through my research.

Drawings are reduced by printmaking or digital editing, before then taking their form. I often print onto textiles and paper using screen print or digital printing processes. In this exhibition, I have printed onto vinyl for the first time, as the works are outside, they need to be durable.

You have a long-running research project, Looking Back | Moving Forward. Tell us more

In 2015, I began Looking Back | Moving Forward, where I researched into examples of 1930s Seaside Moderne architecture in North West England and Scotland through site visits, meetings with local people, historians and archival visits at The Victoria and Albert Museum, RIBA and Whitworth Art Gallery. I was interested in exploring these examples, as architecture of this kind in South England, such as the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill, is very well documented.

I developed this research into new work for shows at In Certain Places, University of Central Lancashire, Preston and Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool. During this time I began a conversation with The Midland about a possible exhibition or project at their site, which seemed really important as it was so central to my research.

What do you hope your ongoing work will achieve or highlight?

I am interested in reviving the notion of utopian idealism at the height of the 1930s exuberance – I seek to interpret and restore this approach my work in new forms. Despite the trauma of World War I, there was a tenacity and determination to rebuild and continue to look forward to the future, an aspect of the human condition which I greatly admire.

Within This Building for Hope, situated within and around The Midland architecture itself, the artwork will focus on revitalising elements of the architect’s original intentions, rather than emphasising decline or decay – embodying and restoring what was once lost in new, temporary interventions to the space.

You also explore post-colonial and post-industrial sites – why this type of architecture?

Although I have many explored modernist architecture in my work since 2014, I’m interested in architectural history, and how buildings are constantly reimagined and repurposed with the hope of creating better living conditions. When I moved to Manchester from London in 2011, I was surrounded by post-industrial architecture that had been repurposed in many forms, which I explored in my work.

From 2012-2013, I went on several visits to South Africa and Namibia, when I first came across post-colonial modernist architecture on the seafront. The architecture had been altered by the current government by painting in different colours or changing use, but still served as a reminder to a troubled past.

Do you have a favourite building? If so, what and why?

Each building is unique in its historical narrative and design and has their own special character. My favourite street, however, is Ocean Drive on Miami Beach which faces the sea. As you look down the street there are numerous different coloured hotels lining the streets painted in tropical, pastel colours.

The seashore is lined with palm trees, which were brought to the area in the 1930s to create a more exotic environment. The street is busy with holidaymakers, relaxed and enjoying themselves, almost performing in a stage set.

](https://www.materialsource.co.uk/uploads/articles/df/dfd3edffa1493b2badd5778b324ed57d95abc7fc_630.jpg)