Graduate spotlight: Paola Barreca, Rooted in Clay.

Image credit: Sophie Percival

Rooted in Clay is a research-led project that explores sustainability and placemaking in architecture through the lenses of craft, culture, and carbon.

Developed by Paola Berraca during her final year on the Architecture MSci course at The Bartlett School of Architecture, in collaboration with Morris+Company, CELLA, UCL East Community Engagement Seed Fund, Lyons & Annoot, Wienerberger, and EHSmith, the project challenges conventional metrics for sustainability by foregrounding community, biodiversity, and material provenance.

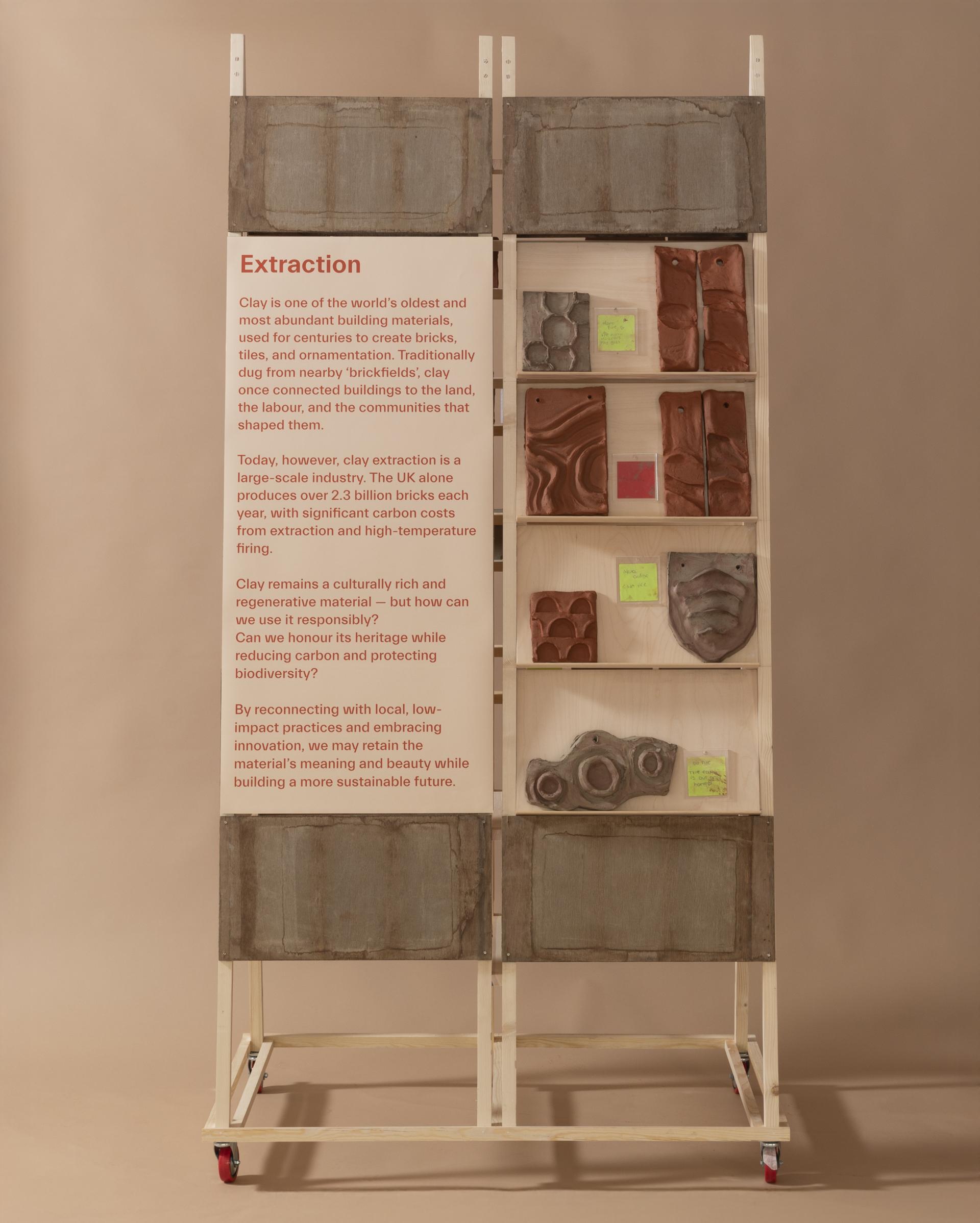

Centred on a series of co-making workshops with students at The City Academy Hackney, Rooted in Clay uses Weald clay provided by Wienerberger, sourced from the Smokejacks quarry in Surrey. Shaped around the three themes, Clay, Culture, and Carbon, these thinking-through-making workshops probe at a more transparent and community focused approach towards the materiality of our built environment.

A material interwoven into the fabric of London’s architectural vernacular, Clay has been utilised for Georgian stock bricks and contemporary façades - embodying continuity, craft, and place. Despite its cultural significance as a material, it’s also implicated in industrial extraction, biodiversity loss, and carbon-intensive firing processes.

The project reconsiders clay’s role in London’s architectural heritage while acknowledging its industrial and ecological impacts. Through hands-on experimentation and participatory design, Rooted in Clay proposes new, place-based models for architectural production that reintroduce craft, care and context into the making of our built environment.

Rooted in Clay was developed in Paola’s practice-based research year in placement at Morris+Company, where she spent part of her nine months with the firm embedded in project work, and the other part developing this research project.

Reflecting on her graduate project, Paola discusses the importance of craft in looking at sustainability more holistically, beyond carbon metrics and product certifications - highlighting the wider considerations of community and biodiversity.

To kick off, can you please introduce us to your collaborative graduate project, Rooted in Clay?

“Rooted in Clay is a collaborative research project that aims to rethink how building products are designed and developed by placing equal value on environmental sustainability and social engagement.

“It does so through setting out a more holistic approach to sustainability in the built environment; one that moves beyond carbon metrics to include craft, community, and biodiversity considerations.

“Using clay as a case study, a material that is embedded in architectural history, local, and regenerative, but also tied to extractive and carbon-intensive processes, the project explores how material choices can become platforms for ecological and community-driven considerations.

“The project questions how participatory and place-based practices can contribute to new models of sustainability that empower local people and support natural ecosystems. Through a series of co-making workshops with The City Academy Hackney, students worked at 1:1 scale to design and make clay tiles that responded to a brief around biodiversity, culture, and carbon.

“These workshops didn’t just produce physical outcomes, they revealed new ways of thinking about architectural production. For example, how to bring back making agency, what shared knowledge is valued, and how materials can connect people to place.

“From this process, four co-making principles emerged: participation, collaboration, crafting, and response to brief, proposing a framework for embedding ecological awareness and community empowerment into product development.

"Rather than seeking a singular answer, the project opens up a conversation about transparency, locality, and shared value in architectural practice; one rooted in materiality, making, and meaning.”

Image credit: Sophie Percival

Image credit: Sophie Percival

How did the collaboration with Morris+Company come about? And what was the approach towards this partnership?

“The collaboration came through the Architecture MSci course at the Bartlett School of Architecture, where my fifth and final year was a practice-based research year in placement at Morris+Company for nine months. I spent part of my time embedded in project work, and the other part developing this research project.

“From the outset, there was a shared curiosity about how materials tell stories: social, environmental, and spatial as well as in exploring a holistic consideration of social value and ecological impact of building materials.

“The partnership was open and iterative; the practice supported me not only with resources but with critical dialogue, testing ideas, and forming an understanding for the real-world architectural context.”

Your project intersects ecological design, craft and biodiversity. Can you tell us why clay was selected as the medium to connect the dots here?

“Clay was selected as a case study for this project due to its compelling relevance: it is a local, low-tech, and ancient material deeply embedded in London’s architectural vernacular, from Georgian stock bricks to contemporary façades, embodying continuity, craft, and place.

“Yet despite its cultural significance, clay is also implicated in industrial extraction, biodiversity loss, and carbon-intensive firing processes, positioning it as both a vessel of heritage and a site of environmental concern.

“Therefore, clay allowed me to explore the environmental footprint of materials, whilst also re-engaging with making as a tactile, communal and culturally rich process. It became both the subject of the research and a tool for learning and making. Something to challenge and to celebrate.”

In what ways can clay products support biodiversity in the built environment?

“There is still a lot to explore with regards to clay products’ ability to support biodiversity in the built environment, yet the current market includes products designed intentionally to provide habitats within building envelopes, including tiles or bricks that host birds, bees, bats or bugs.

“In the research, we investigated the opportunity to rethink the whole material life cycle of clay. For example, how can clay extraction sites be treated and remediated as biodiversity havens? How can surface textures incorporated within building designs encourage moss growth or water retention? This project began to test these ideas with the student-made tiles, embedding biodiversity principles directly into their form and function.”

Image credit: Sophie Percival

Image credit: Sophie Percival

There are also strong links between making with clay and community. Why do you think this is? And how did this inform your project?

“Aside from its rich historical role in England’s architectural heritage, making it a recognisable and defining material, clay is also uniquely democratic. It is responsive, intuitive, and tactile; almost everyone has encountered it in some form.

“Its ability to be moulded at a 1:1 scale makes it immediately accessible, allowing participants to work directly with the scale and materiality of the architecture they are learning about. In this project, and particularly in the workshops, that accessibility helped question traditional hierarchies between ‘experts’ and ‘learners.’

“The workshops invited local students not merely to observe and learn about architecture, materials, and sustainability, but to engage with it through making. They shaped, carved, and experimented with the materials of their environment. This approach reinforced the idea that sustainability is not only technical, but also cultural, collective, and grounded in shared experience."

Can you please talk us through your approach to running the co-making workshops?

“The co-making workshops, with nine secondary school children from The City Academy Hackney, were framed around three themes: Clay, Culture, and Carbon.

“The first workshop was held in the students’ classroom, introducing them to the environmental impact of clay: from extraction to firing, as well as encouraging the students to begin exploring using clay to collaboratively make patterns and textures through play.

“The second took place at Morris+Company’s studio, where they worked at 1:1 scale using pre-extruded clay tile bats provided by Wienerberger. Students were asked to respond to a design brief about biodiversity and culture, crafting tiles that could provide habitats or communicate environmental and local stories. It was equal parts making, learning, and reflecting, allowing students to work together and learn from their surroundings.”

Image credit: Sophie Percival

Image credit: Sophie Percival

Why was the participatory model 'Learning through making' important to the research?

“Inspired by educational theorists like John Dewey, ’Learning through making’ theories foreground the active and tactile material experience over abstract theory and passive learning.

“In this research, it forms an inclusive models that creates space for agency in which learners become co-designers, not passive recipients. It was crucial that students weren’t just taught about sustainability but could experience it through negotiating carbon decisions, understanding clay’s properties, and shaping tactile outcomes.

“This philosophical model revealed a framework for how participatory processes can embed both environmental understanding and social value into product development.”

And what were some of the standout findings from the co-making workshops?

“One of the most powerful outcomes was witnessing students’ growing confidence and agency within the objects they were making. At first more hesitant, by the second workshop students were discussing designing tiles moss textures, bird habitats, and even carbon footprints with clarity and creativity.

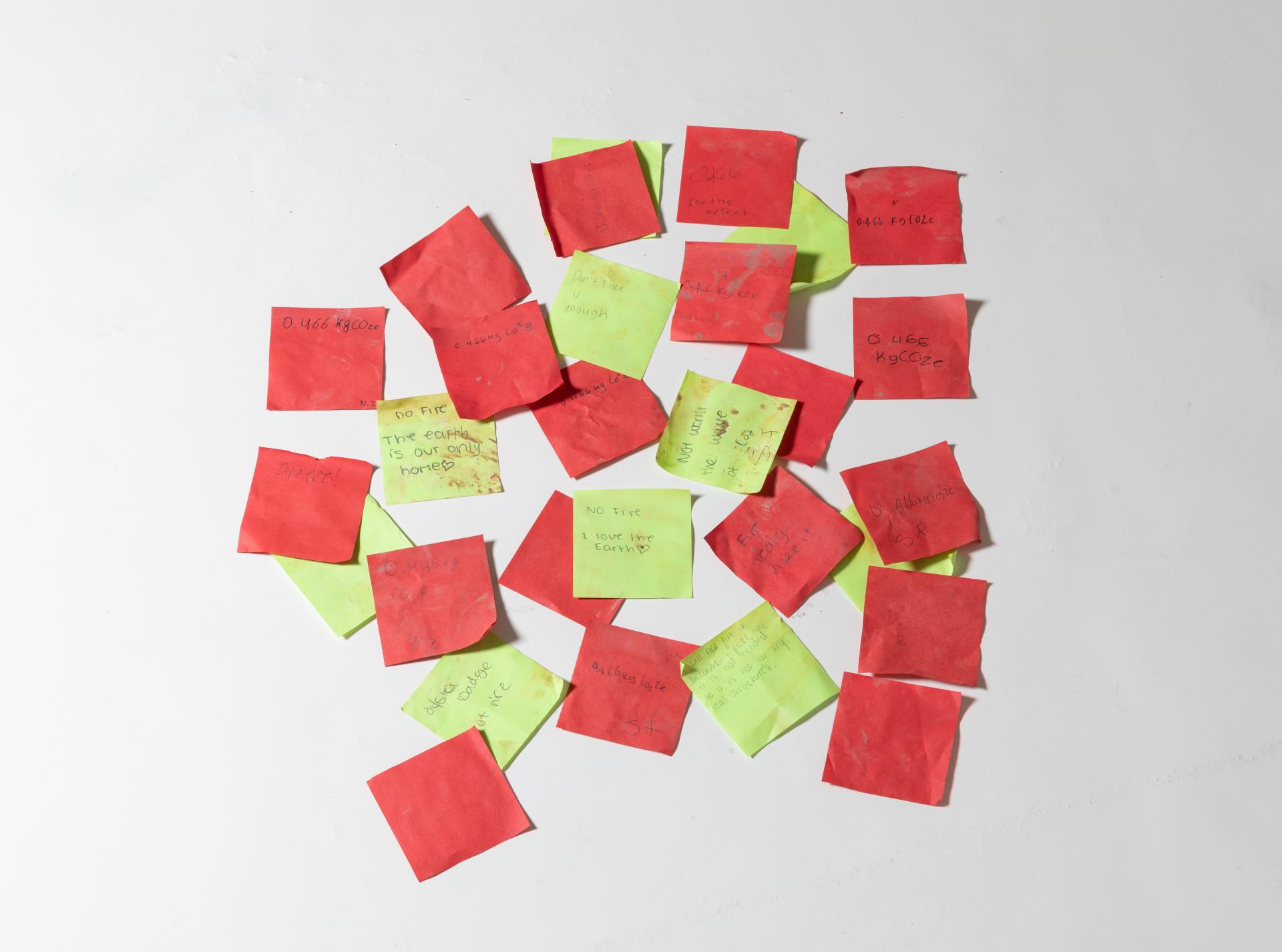

“Their tiles ranged from poetic to practical as some incorporated micro-grooves for moss retention, while others told cultural stories through carving. At the end students were given the choice to fire their tiles or not through a series of post-it notes. This revealed critical environmental learning and thinking, with many opting not to fire due to carbon concerns. These moments reflected a real shift in authorship and awareness.”

What kinds of clay bodies did you use and why?

“We worked with Weald clay provided by Wienerberger, sourced from the Smokejacks quarry in Surrey. It was chosen for its local relevance and its ties to the regional brick-making tradition.

“Using this specific clay made the workshops feel more grounded and allowed for conversations about material origin, extraction impacts, and the invisible histories embedded in our built environment.”

Image credit: Sophie Percival

Image credit: Sophie Percival

How did the decision to fire or not to fire impact the material's ecological footprint?

“Firing clay is incredibly carbon-intensive, and one of the most studied difficulties with the sustainable use of clay in building materials, requiring high temperatures and long energy input. As part of the workshops, we introduced this to students, asking them to reflect on the carbon consequences of firing. They then made a decision about each of their completed tiles: fire or not fire?

“This simple act became a powerful way to teach about ecological trade-offs, and it mirrored real-world design choices. Several students opted not to fire, seeing it as unnecessary for a conceptual prototype that would “not be used on a real building”. Others saw firing as a way to preserve their work long-term. Both responses were valid, and both showed deep engagement with the learning aims of the workshop.”

The use of industrial manufacture has in some ways distanced architecture from its material roots. How does your project address this disconnect?

“Rooted in Clay attempts to bridge the gap between industrial manufacturing methods and the material roots of architectural products, bringing the human hand and its cultural history back into dialogue with material processes.

“Industrialisation has distanced us from the origins of the materials we build with, often masking their social and ecological costs. By reintroducing craft, narrative, and co-design into product development, the project proposes a more transparent and ethical approach.

“It’s not about rejecting industry, but about embedding community, care, and context into the process.”

Image credit: Sophie Percival

How do you envision these tiles functioning in an architectural context?

“The tiles made in the workshop have become an example for a different and more collaborative approach to building product design, yet they could be integrated into façades as both aesthetic elements and biodiversity-supporting devices. Their designs incorporate texture, voids, and/or planting features could support insects, mosses, or birds in urban settings.

“However, more broadly the project proposes a new process model where tiles and other materials are co-designed with local communities, embedding storytelling, sustainability, and participation into the very fabric of our buildings.”

What are some of your key learnings from your collaboration with Morris+Company?

“Working with Morris+Company taught me the value of applying research in a live practice context, especially how research and practice can exist in a more fluid exchange, especially when both are driven by curiosity and care.

“In both working and researching, architecture became framed not just as the design of buildings, but as a broader practice rooted in material, social, and ecological relationships. The collaboration encouraged me to research beyond disciplinary boundaries and to explore biodiversity, craft, education, and cultural memory as essential components of design.”

How will this project influence your wider architectural practice?

“This project influenced a vision of architecture that is beyond the discipline of buildings, but a system of materials, and people. My wider architectural practice will continue to attempt to engage with local communities as it enriches architectural thinking in designing for and with people in a way that honours place, voice, and participation throughout the process.

“Moving forward, I want to continue working at the intersection of craft, sustainability, and participation whether through building design, public engagement, or speculative research.”

Click here for more information on Paola’s graduate project, Rooted in Clay, as well as a number of other graduate projects from The Bartlett Summer Show 2025.