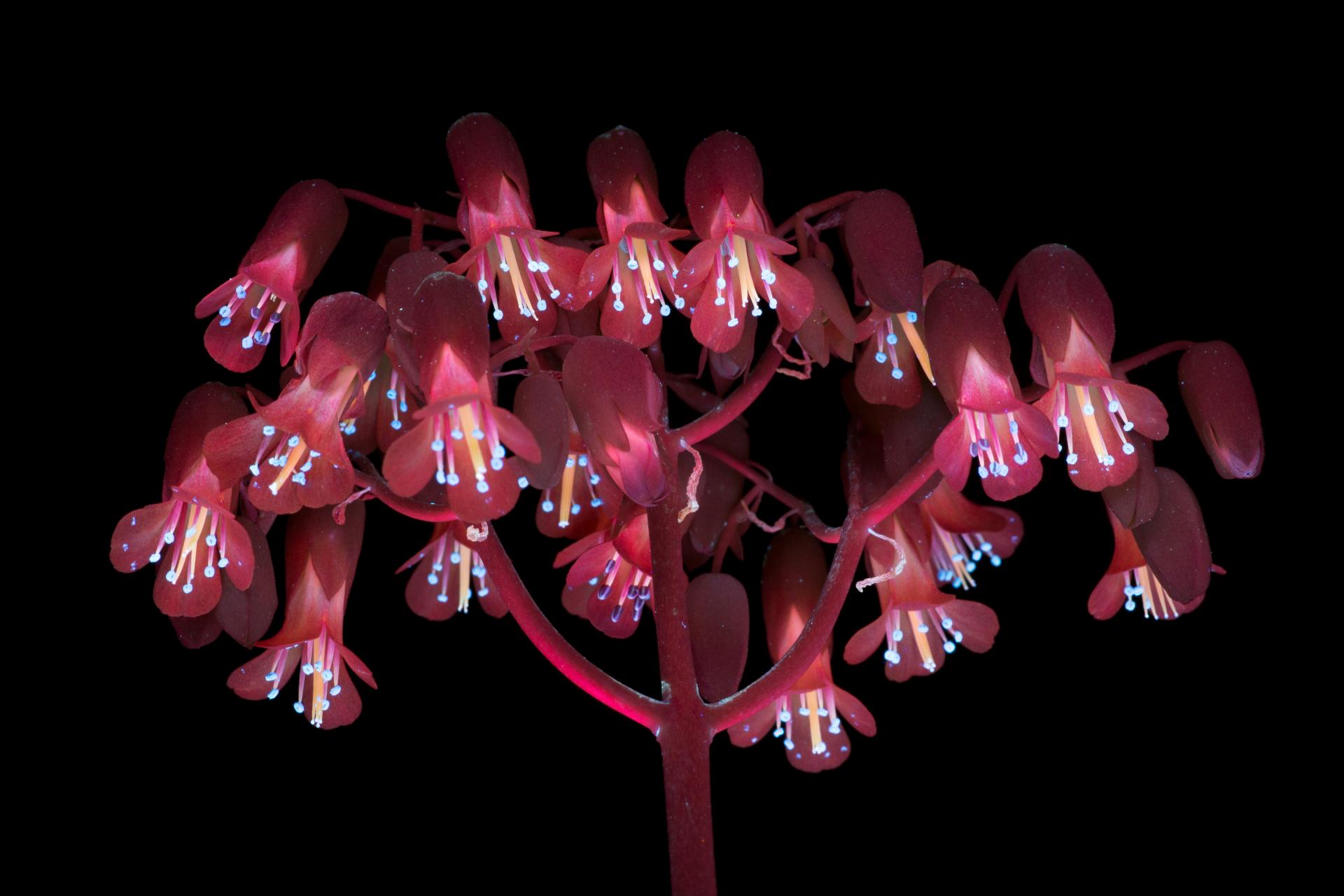

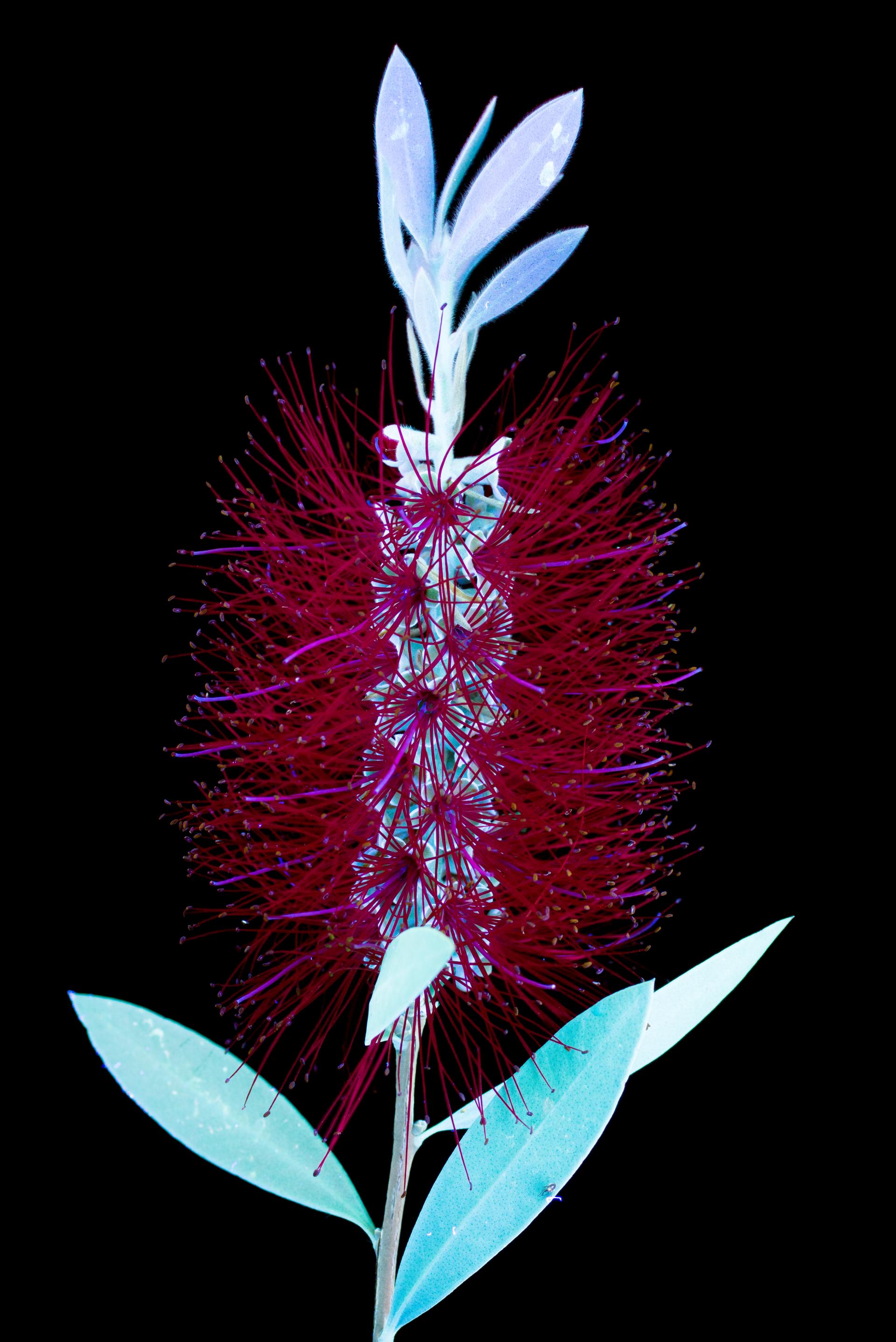

In conversation with photographer Craig Burrows - author of What The Bees See.

Image credit: Craig Burrows

When we set about exploring the relationship between EDIB and sustainability for our latest instalment of Material Moods, calling on the ultraviolet photography of Craig Burrows took us down what may seem an unusual path.

But often, the best inspiration isn't taken directly from your sector or discipline in order to innovate, it's a side step away, sometimes leading to the most unlikely of places.

Craig Burrows is a UVIVF (ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence) photographer. Harnessing this technology to capture botanicals, Craig creates otherworldly images from the perspective of the honeybee - pollinators are believed to see in ultraviolet.

Through his imagery, he unveils a unique signposting system of ultraviolet induced fluorescence that symbiotically directs bees to nectar and plants to pollination. It is a world that is vivid, glowing and mesmerising, all while being entirely practical. A fine tuned balance between beauty and utility.

By presenting flowers in a beautiful and novel way, his aim is to inspire thought about the history and partnerships between plants and their pollinators. "Since most media we consume these days is visual," he puts, "I think visual storytelling is essentially mandatory for environmental awareness and conservation."

Craig's work opens a visual dialogue on what it is like to see from another's perspective. It is, of course, an essential aspect of any new interior design, or architecture project. Just as EDIB encourages us to put ourselves in another’s shoes, ‘What the Bees See’ - a book by Craig P Burrows published by Chronicle Books - encourages us to do the same.

Here we chat to Craig about his photography practice to date, the insight and environmental messaging behind What The Bees See, and the power of visual storytelling in environmental awareness and communication.

Firstly, can you please introduce us to your photography practice? How did you get started?

"I grew up in the era where digital photography was in its infancy and ever since the first digital backs were available I was interested. It wasn’t until around 2010 that I would say I took photography seriously and bought my first (used) camera equipment on eBay while in college.

"I dabbled in all genres at first and was especially drawn to unusual forms of lighting such as infrared and around 2014 I came across the genre known as UVIVF (ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence) and fell in love.

"In 2017 I decided to submit my work to be considered by 'This is Colossal' who elected to feature it in a post which is the moment I would say I transitioned from hobby to something perhaps resembling a career in photography."

What is UVIVF photography? And how does the process work?

"UVIVF is a specialised branch of photography which uses ultraviolet (UV) light to excite the matter composing a subject which in turns results in Inducing Visible Fluorescence (IVF). In short, higher energy UV photons are absorbed, some energy is dissipated in the molecules, and then photons are shed at various longer wavelengths than the ones which caused the excitation.

"Excitation by high energy particles including photons is critical in many technologies, particularly those pertaining to illumination, so this is one aspect of it that has been enabled through the advancement of and decreasing cost of ultraviolet LED sources. Previously it was largely used in forensics rather than being applied to biology and botany."

Image credit: Craig Burrows

Image credit: Craig Burrows

Image credit: Craig Burrows

Can you describe the spectrum we're experiencing in your works? What determines a flower's colour or fluorescence to differ from another?

"While the energy source in my photos is an ultraviolet LED, the spectrum of the light being recorded is explicitly visible. Any wavelength longer than the source is possible meaning a long-wave UV source can produce blue through red and even infrared though we cannot see it.

"Different compounds respond differently to light which is how we end up with colour in general. The different pigments, polymers, simple sugars, etc., all absorb the UV and release different wavelengths depending on how their molecules respond.

"Some are able to absorb UV and release more intense visible radiation while others are highly reflective or absorb the UV and don’t produce much visible fluorescence as a result. Some of these results are simple byproducts of producing a colourful pigment, some just being fluorescent sugar (nectar), and some may be used by a plant to protect their cells and DNA from damage much like melanin in human skin. Highly fluorescent pollen is likely the latter case where the UV is transformed and released so that it can’t damage the fragile genetic material inside."

Can you please tell us how the UV light spectrum guides bees towards flowers that contain nectar and pollen?

"Pollinator vision is a very complicated topic and there’s MUCH to be learned. Even so, it’s an exciting frontier and I’m looking forward to seeing what is uncovered in the future. What we do know is that bee vision is wildly different from ours for several reasons: Compound eyes; Bees see ultraviolet, blue, and green, while humans see blue, green, and red; Bees have a natural ability to discern polarisation of light.

"The most significant thing is perhaps their ability to perceive ultraviolet light and flowers exploit this by showing patterns only visible when looking at reflected ultraviolet (UV-R) (and sometimes UVIVF) images.

"The classic example is a “nectar guide” bullseye in a sunflower where to us the flower looks all-yellow but a bee sees a dark band in ultraviolet in the centre. Furthermore, bees are extremely attracted to blue light in particular and in the case of sunflowers there is blue fluorescence in the florets at the centre, which combined with the reflected UV and blue+green means they would see nearly pure blue there even if it is dim.

“This pattern of blue fluorescence in the reproductive anatomy of flowers suggests to me that it is being employed as one component of attracting bees, and perhaps other pollinators."

Image credit: Craig Burrows

Image credit: Craig Burrows

Image credit: Craig Burrows

"By presenting flowers in a beautiful and novel way, I want to inspire thought about the history and partnerships between them and their pollinators whether they’re wasps, bees, or beetles."

How did the idea of seeing from a bee’s perspective become a lens - literally and metaphorically - for you? What does that shift in perspective unlock for us as humans?

"I find flower-pollinator interactions fascinating, whether it’s trickery in orchids, mechanical denial to small less useful bees, or the simple mechanisms that draw them in. Reflected-ultraviolet is something I dabbled in when I was doing infrared photography but I didn’t find the results as exciting and engaging as the world of UVIVF.

"Luckily, UVIVF intersects with the world of UV-R where sometimes nectar guides show up as shifted colours in UVIVF. There is also the factor that to produce fluorescence, the flower must be absorbing ultraviolet which means some of the fluorescence is directly the result of those same patterns in the UV-R.

"While UVIVF is far from a 1:1 representation of bee-vision, it has enough intersection to be useful and produces really stunning imagery that humans can use as a jumping-off-point to imagine how bees might perceive flowers and learn more about how their senses work on the whole."

We often talk about saving the bees but not necessarily understanding the world from their perspective. Please tell us about your goal to cultivate deeper understanding and empathy through giving a glimpse into their world.

"My feeling is that modern human culture both intentionally and unintentionally drives a wedge between our individual experience and the ‘natural world’ we are supposed to be a part of. The fundamental macroscopic components of the natural world which support other life on earth are plants and their pollinators, but I think there is a terrible disconnection which causes most people to ignore if not actually disdain them.

"By presenting flowers in a beautiful and novel way, I want to engage the viewer in thought about these green things usually taken for granted and inspire thought about the history and partnerships between them and their pollinators whether they’re wasps, bees, or beetles."

"Since most media we consume these days is visual, I think visual storytelling is essentially mandatory for environmental awareness and conservation."

Image credit: Craig Burrows

Image credit: Craig Burrows

Image credit: Craig Burrows

What environmental changes do you hope to see spurred from What the Bees See?

"Even within my own lifetime I have seen the decline in insect populations. It was impossible to go on a road trip without resulting in bugs being splatted on the windshield. While that’s obviously not a desirable outcome, the lack of splatted bugs is demonstrative of the tremendous decline in their populations.

"Every year we hear about the decline of the monarchs, about pesticides poisoning bees, about deforestation crippling agriculture because even gnats and midges are dying off. By invoking an element of these creatures’ beauty, it is my hope that the readers/viewers will see the value in preserving them which requires consideration for the environment at large."

How much of a role do you think visual storytelling can play in environmental awareness and conservation efforts?

"Since most media we consume these days is visual, I think visual storytelling is essentially mandatory for environmental awareness and conservation. That isn’t to say that writing and information isn’t important, but the visual component provides the impact and excitement, cultivating the curiosity required to get a viewer to engage with the details.

"The content has to almost be a slap to the face to stand out in a series of other swipes and scrolls if it is to have any impact on a viewer."

If readers come away with a deeper appreciation for bees, what's one action you hope they might take up as a result? And what positive changes would you like to see specifically in the built environment?

"Because it is so hard for individuals to effect change at scale (such as preserving 100 hectares or banning pesticides), the best change I perceive is engaging in those activities at home at individual scale. Things like replacing water-hungry lawns with native gardens where only pollinator friendly pesticides are used can make a big difference if done in small spaces with great quantities.

"Besides the environmental benefits of creating native micro-habitat, it is a personally enriching experience and is a beautiful gateway to experience the wild world at one’s own pace from the safety of one’s own home.

"From Epictetus’ Enchiridion to the Serenity Prayer commonly used in ‘anonymous’ meetings, there have been 2,000 years of philosophers writing and speaking about learning to change what we can and to accept the things we cannot change, and I think this applies here. It’s worth caring about what is happening at large scale, but we should never give up and should put effort into doing whatever we can with the opportunities we individually have."

Image credit: Craig Burrows

Image credit: Craig Burrows

Image credit: Craig Burrows

Discover more about Craig’s practice here, and explore our Vitality palette in full here.