Natsai Audrey Chieza of Faber Futures on biodesign, growing microbes and sustainability

Portrait by Toby Coulson

It is safe to say that Natsai Audrey Chieza’s job is not run of the mill. A materials designer who has dedicated eight years of her life to working in the field of biodesign, Chieza founded Faber Futures in 2018.

At the heart of the biodesign consultancy and creative research lab is the belief that the answers to some of the biggest challenges facing this planet can be found in nature: "What if we could harness the inherent intelligence of nature to make things with living systems?"

In Chieza’s eyes, biology is the next technological frontier. By learning from living systems and integrating design, biology and technology, Faber Futures’ mission is to identify and initiate holistic pathways to sustainable material futures. Think of it as planet-centred product development.

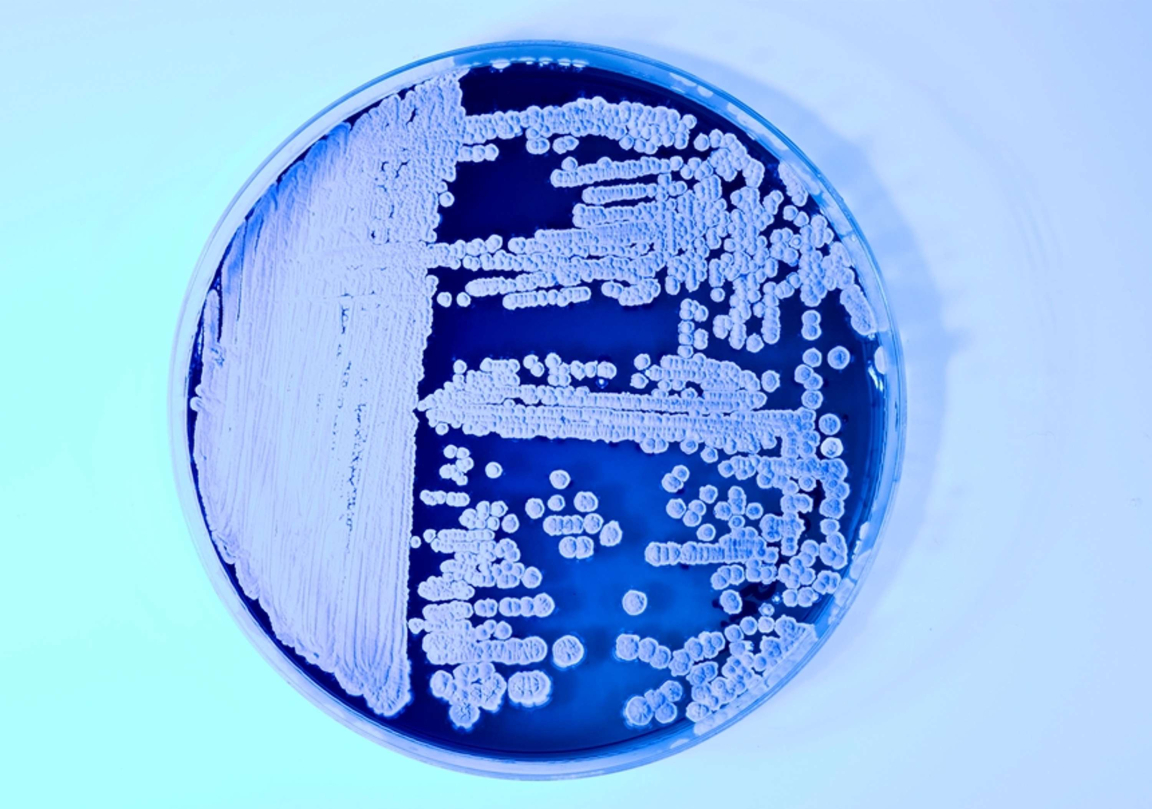

Through its global network of biotech labs and collaborators, Faber Futures draws on the biofabrication possibilities presented by organisms such as bacteria, fungi and algae to develop new materials, strategies and applications across a spectrum of industries – from fashion to viticulture. We spoke to Chieza about this and much more.

Faber Futures’ area of operation is rather complex, could you sum it up in a sentence?

We fuse design thinking with biotechnology to grow sustainable materials, products and services.

What inspired you to set up a studio instead of continuing your work as an individual? Was there a eureka moment?

I’d been working independently as a designer in-between the disciplines of design, biology and technology for seven years. Presently a synthetic biology industry is emerging on a platform of potentially transformative biological materials. It feels as if it’s the right moment to open up the thinking we’ve developed over many years to industries that are showing a willingness to shift their manufacturing processes towards the circular economy.

Biology is our next technological frontier. At Faber Futures we believe that design will play a pivotal role in making this a reality, and it is there where we think we can add value.

What sort of brands and businesses does Faber Futures set out to help?

We are pretty sector agnostic and work across industries to enable collaboration around ideas that we feel are important – things like sustainability and distributed equity.

That means we are working with actors across the value chain: chemical and textile manufacturers, fashion and apparel brands, consumer biotechnology companies, and research labs. We see this as being very important in understanding the complexity ahead which opens up our capacity to design for a system-wide change.

What kind of services does it offer them?

Because of our network of collaborators and partners, our LAB is highly responsive to our clients' needs. We offer design-led protocol development for early-stage innovation, tapping into our international network of synthetic biology, material science and design.

We are working with a lab that's engineered a bacteria to do something entirely novel on a petri dish. And we are equipping that lab with the tools and language to contextualise its findings, identify multi-sector application routes and clear pathways to scaleable, circular design. This approach is incredibly important as more companies begin to engineer biology for the consumer market.

We also build bespoke masterclasses, curatorial projects and special projects for our clients who have to make sense of this emerging landscape and communicate both internally and externally across their value chain. We are never prescriptive about our approach because actually, that’s not how biology works. Every client need is unique, and so are opportunities for biofabrication that speaks to their needs.

When I am in the lab growing microbes that do pretty remarkable things, I am especially enthusiastic and optimistic about the future.

A lot of people are inherently suspicious of biotechnology and biodesign, seeing them as ‘meddling with nature’ in some way – how does Faber Futures differ from that caricature?

The story of human collaboration with nature precedes the fourth industrial revolution: the convergence of nano, bio, computational and information technologies. This complexity should give us pause to reflect on the kind of world we want to build over the next century.

This zone of friction is really fascinating to us because it represents both the unknown and the potential to shape it into alternative futures. So we've immersed our practice with those problematic questions, taking a critical and practice-based approach that focuses on interventions that align with our values on the ecological stewardship of this planet.

The human story is one of technology and intervention in our natural environment, bending it to perform our own ‘higher’ needs. I think that culturally, and specifically in the industrialised global north, there’s a collective realisation that working with nature may be a more holistic approach than extracting from nature.

Scientific discoveries on the link between our microbiomes to our gut and brain health illustrate that to make with life, therefore, is not just about building things from living things – it's making sure that when we intervene on living matter, we are actually thinking about the system in which that technological power exists.

Through the projects we are working on right now, we engage with the ecological, economic, and societal parameters of industrial biotechnology. We believe that we have an unprecedented opportunity to work with biology to reimagine our terms of engagement with it: to re-think the kind of relationship we wish to have with nature. Simply, we are nature, and it is us.

Coming from an architectural design background, how was your experience of moving into the realm of ‘the sciences’? Do you think there’s a stronger interest in interdisciplinary collaboration that there used to be?

In recent times we’ve seen the effects of cultural bubbles on society, so I don’t think intellectual ones are any more progressive. My path between architecture, material futures and biology has been a winding road that has sort of held me captive! When I started out there was no blueprint.

I’ve had to formulate the language to travel between these disciplines through my practice, learning from experience to be able to determine my own terms of engagement. Intuition has played a part, but it has been instrumental to have a handful of peers, advocates and believers to show that this road less travelled could be both rewarding and meaningful.

Today, there is definitely more widespread momentum towards interdisciplinary collaboration. I’m on the founding team of the Ginkgo Creative Residency at Ginkgo Bioworks, co-curating a space within its foundry to facilitate the exchange of these types of knowledge.

These kinds of initiatives happen because of a network of edge dwellers who aren’t afraid to take risks and see the value in thinking differently. If more people could seek open-mindedness, and resist the urge to live and think in silos, that’s one step towards making an impact on some of the enormous challenges we face.

Given the scale of the ecological challenges we face today, how optimistic are you about the future?

When I am in the lab growing microbes that do pretty remarkable things, I am especially enthusiastic and optimistic about the future. This can shift when you recognise the scale of the challenges facing the planet today and that no single technology, discipline, or idea can fix them.

So at that point, I become a little more pragmatic. Where despair can set in, is in seeing how the technosphere is entangled with our shared biological, socio-political and cultural histories. So I make space in my life to live, to act, to change – that is a commitment to the future which cannot happen without some level of optimism.

Is there a particular strand of Faber Futures’ research that you’re especially excited about right now?

I’m really excited at what it means to design interactions, experiences and solutions to problems at the molecular scale, and how this is married to the realities of social, economic and geographical contexts.

We are working on projects with fashion and apparel brands to explore what it is to scale bio-pigment dyes for textiles for different scales of production. Growing pigments in the lab is incredibly resource and energy efficient but there will be biological limits to scaling this to the human scale. We want to define those parameters and learn how to design and thrive within them.