Rameshwari Jonnalagadda presents TerraMound: A clay 3D printed solution for the efficient cooling of buildings.

Emerging from the Bartlett School of Architecture’s esteemed Design for Manufacture course, Rameshwari Jonnalagadda is the pioneer behind TerraMound - an ecologically driven, natural cooling system for the built environment.

With climate-stimulated temperature increases now at critical cause for concern within the built environment, it’s reassuring to spot graduates tackling these topics within their thesis projects.

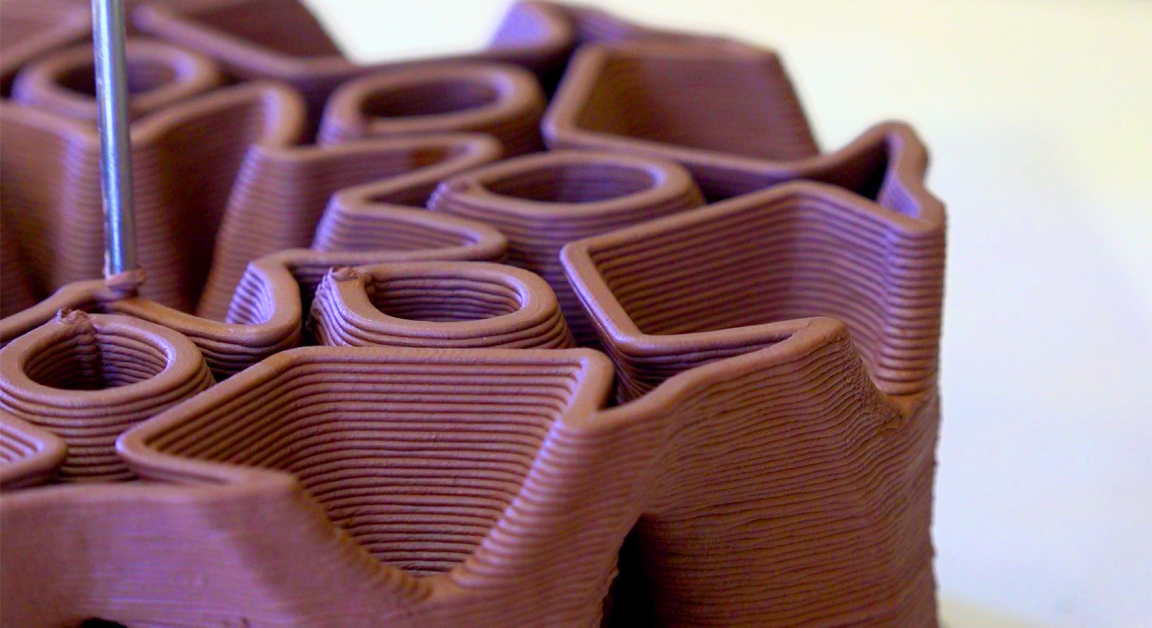

Using earthenware terracotta and 3D printing technology, Terramound consolidates Rameshwari’s understanding of mathematical geometries known as ‘minimal surfaces’ to create a system of porous networks - envisioned as a planter - that produces a cool breeze and ventilates the surrounding space.

With the visual appeal of a work of art, whilst also offering a host of potential beneficial features, such as bio-receptivity and acoustic control, TerraMound quickly captured our attention at the Bartlett Fifteen Show.

Keen to find out more, we sat down with Rameshwari to discuss her inspiration for exploring mathematical geometries as a means to cool our buildings, TerraMound’s design process, and her future-thinking aspirations for the application of TerraMound in the built environment and beyond…

Can you please introduce us to your graduate project, TerraMound?

“Imagine having a little sculpture on your desk that makes a cool breeze. That's TerraMound! It takes its inspiration from termite mounds.

“I used 3D printing with clay, while integrating mathematical geometries called ‘minimal surfaces’ to create these artistic shapes, with porous networks to bring this conceptual idea to life. Water drips down from a planter on top, soaking the clay, and when the water evaporates, it creates a refreshing breeze. It's a beautiful way to stay cool and ventilate your space.”

What drove you to investigate this for your thesis project?

“Minimal surfaces are fascinating mathematical geometries with high surface area and are great at handling heat while creating lightweight structures. They're used in high-tech fields like aerospace and medicine. I wondered if we could apply these shapes to the built environment. Asking questions like, what possibilities could they unlock? Could they be used to cool buildings? TerraMound was my exploration for this.”

How can 'working with mathematical geometries with minimal surfaces' create efficient cooling solutions? And how did you draw parallels with between this and termite mounds?

“Minimal surfaces in TerraMound have lots of surface area, so they let air touch the wet clay. This helps the water evaporate quickly, which cools the air down fast. Moreover, the shapes can also be designed with complex tunnels, inspired by how termite mounds work.

“This means TerraMound, when scaled up, with its porous network, can bring in air without needing extra fans, which makes it a more eco-friendly way to stay cool.”

How does using earthenware terracotta clay help with this?

“Terracotta clay is like a sponge; it soaks up water well. When the water evaporates from the clay, it cools the air around it, just like how sweat cools you down. This works especially well in dry places because the water keeps evaporating, making the air cooler.”

Can you briefly take us through your design and making process with the TerraMound project?

“Working with minimal surfaces for TerraMound was both challenging and fulfilling. These shapes, with their bridges and overhangs, posed printing challenges, but each mistake taught me something valuable.

“I started by creating and refining designs, translating them into computational models. Figuring out the right material thickness and setting up the fabrication process were critical. Watching the printer layer each design was mesmerising, almost like experiencing ASMR.

“After printing, I carefully dried and fired the clay pieces in a kiln for strength and durability. The entire process—from initial design concept to the final firing—was a mix of innovation, problem-solving, and joy in seeing ideas come to life.”

What kinds of practical applications within the built environment could we later see TerraMound in?

“While TerraMound uses a fan in its initial prototype, the true potential lies in its ability to transform buildings into structures that breathe. It could inspire walls that could act as ventilation systems to cool the space down. These walls could adapt to manage heat, air, and light making buildings more energy-efficient and comfortable.”

What do these minimal surface geometries offer beyond temperature regulation?

“Minimal surfaces come in a whole family of shapes, each with unique strengths. Imagine them like a set of Lego, but for grown ups. By tweaking these shapes, porosity and the materials we use, we can unlock a world of possibilities beyond cooling. We can integrate uses like light weight structures, light control, acoustic control, increasing bio-receptivity in designs to name a few. It's exciting to think about all the possibilities.”

What other avenues are you keen to explore in the future?

“I'm excited about the endless possibilities that minimal surfaces and 3D printing offer in design. In the future, I envision creating designs that push the boundaries of geometric freedom and material innovation.

“Whether it's exploring new forms that enhance sustainability and efficiency, or experimenting with bio-inspired design to integrate natural elements into the urban environment, to increase bio-receptivity, my goal is to continue using these technologies and geometries to create designs that are functional, inspiring and impactful.”

What are some key take-away lessons you have learnt during your time on the MArch course that you will carry with you throughout your career?

“The MArch course taught me to see design and making as a fluid process. I learned to embrace failures as valuable feedback and to understand materials and processes better. Turning ideas into real objects became a source of joy for me, and I'm excited to keep exploring and creating . I would like to thank my tutor, Arthur Prior, for his encouragement and support in making this thesis a success.”

Click here to dive further into Rameshwari’s project, TerraMound.