Matthew Raw on tiling stories, post-industrial Manchester and working with clay

Photography by Marina Castagna

Matthew Raw is a ceramic artist who is exploring the possibilities of clay and hoping to challenge public perceptions of what it can do as a material. Based in East London, he is a co-founder of Studio Manifold in Hoxton, an artistic collective of nine Royal College of Art graduates, and has participated in group shows, collaborative projects, and exhibitions in London, Munich, Copenhagen, Detroit and more.

He collected the Jerwood Prize in 2014 for 'The Shifting Spirit', a full-size interpretation of a tiled pub exterior now on permanent display at the Five Points Brewery in East London. He has recently been working with architecture collective Assemble for an Art on the Underground project at Seven Sisters Underground station. Matthew also runs practical public workshops in ceramics via rawceramicworkshops.com. We spoke to Matthew about his work and choice of materials.

Tell us about where you studied and how you've got to where you are now

My BA was in Brighton on the ‘Wood, Metal, Ceramics & Plastics’ course. It was super workshop based, and I got a good understanding of lots of materials and processes, and how to translate ideas into 3D objects. After graduating in 2006 I moved back to Manchester for a year, before heading to Denmark to do a six-month-long residency. That’s when I became serious about using clay, and got onto the ‘Ceramics & Glass’ MA at the Royal College of Art, graduating there in 2010.

Did you always have a love of clay?

Not at all. The art department at my high school didn’t waver much from drawing and painting, and clay needs space and mess to exist comfortably, which for some reason ruled out six-form and foundation. It was only really on my degree that I had a proper go with clay, which I chanced upon because of the multi-material nature of the course. It was its immediacy that instinctively drew me to it – you can shape anything, or an interpretation of anything, just by manipulating a ball of mud!

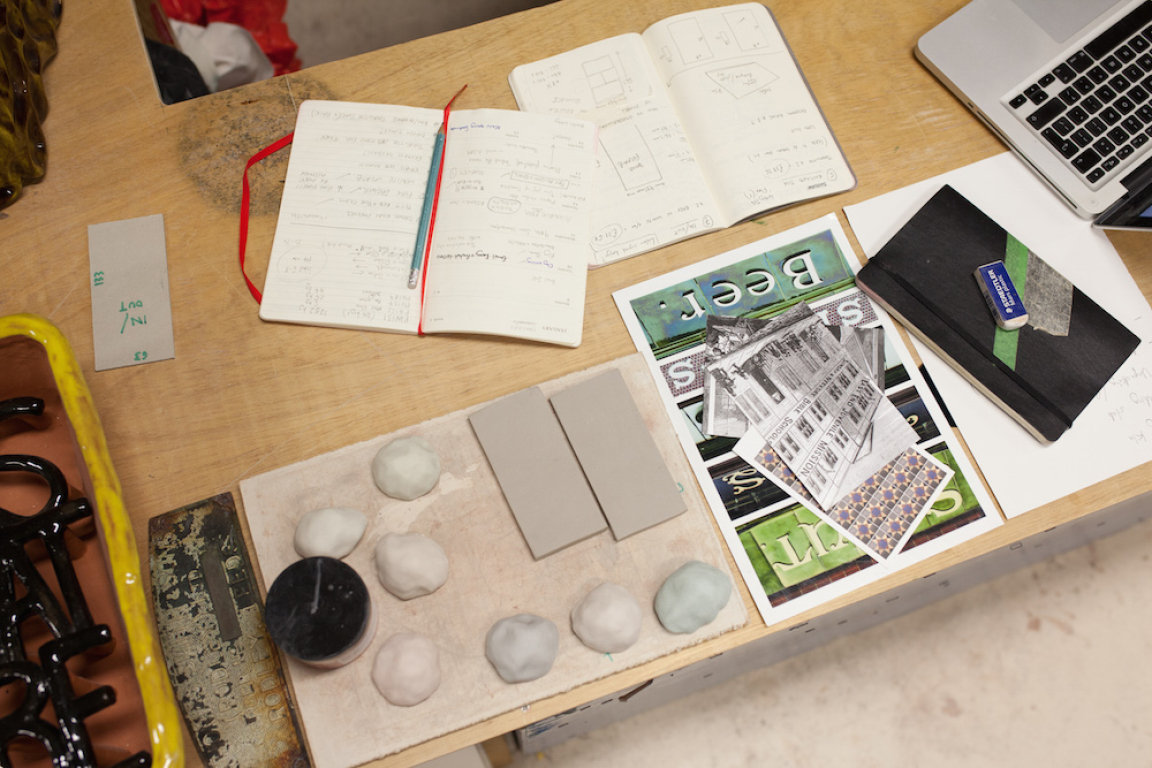

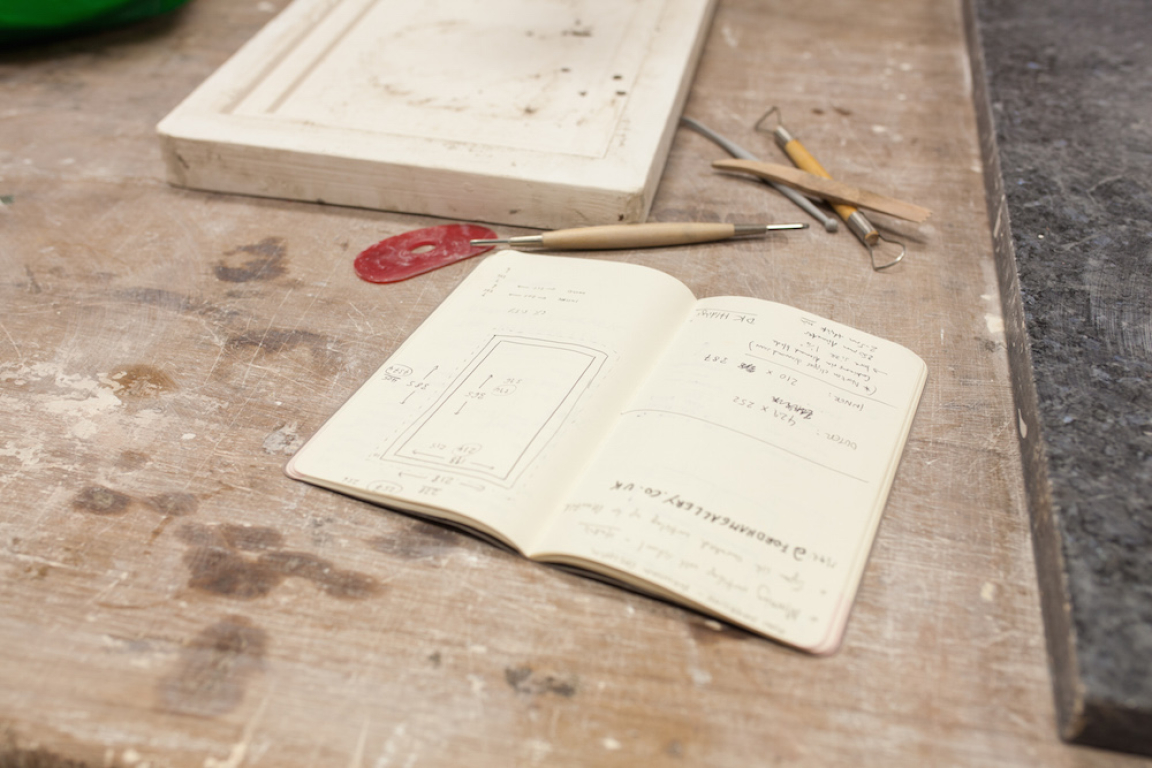

Describe your process, how does an idea transform into a finished product?

My work always starts away from the studio. What am I thinking about, what do I want to convey? And then how can that translate into an interesting and eye-catching object? The majority of my time is spent working with clay, so naturally, that crops up in my thinking more often than not, but I try to stay open and let the idea lead, and over the years have also made work with wood, resins, and paper.

What is it about tiles that interests you in particular?

It is ‘urban grids’ that I am particularly drawn to. Brick walls, tiled façades, paving, etc. I have come to realise that growing up in post-industrial Manchester has shaped this appreciation and aesthetic interest. A pre-Christmas visit to Lisbon really hammered home to me the international and historical significance that tiles have.

Living in London surrounded by such a variety of interior and exterior architecture and building techniques provide me with a constant inspiration, as does travelling the Tube, which further localises my research.

Are your works all of a similar scale/level of complexity?

How long does each take to make? All of the works take different amounts of time to produce. Most of them are made up of multiples, so it means a lot of juggling in the production stage. Every piece is hand-made through a variety of techniques – press-moulded, rolled, scratched, carved, slab-built and coiled work combine to produce the pieces at the making stage.

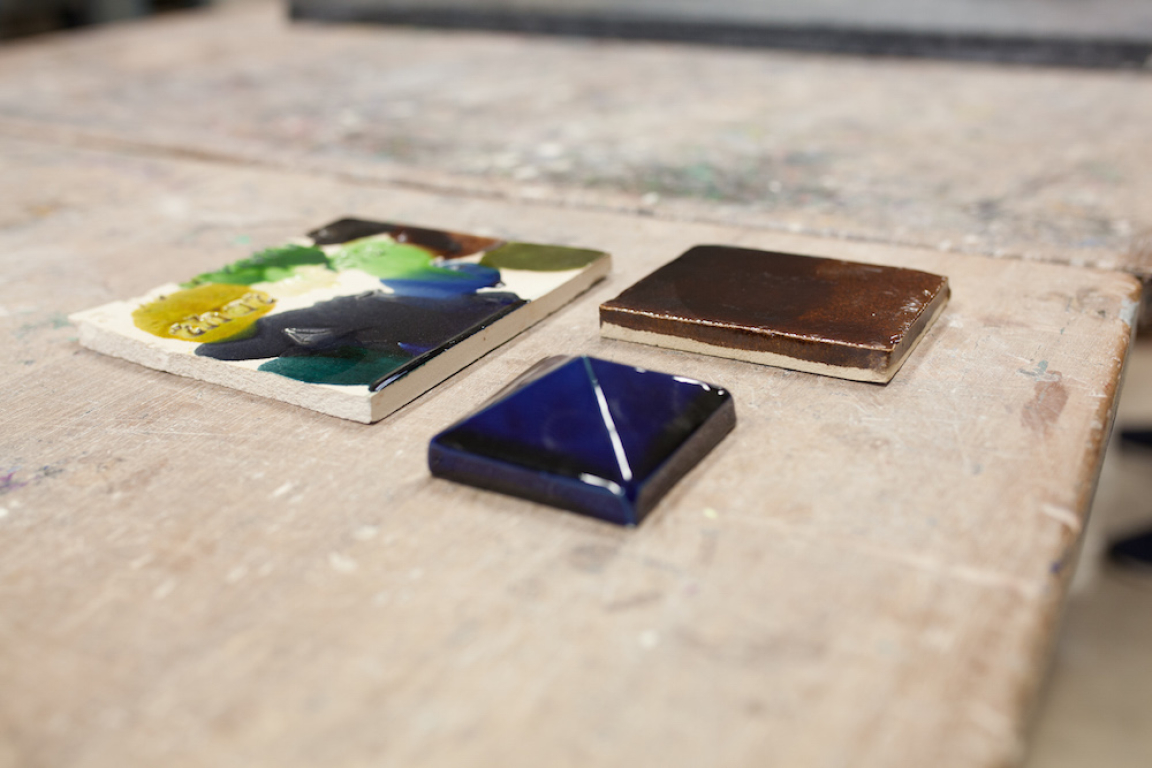

I then have to factor how to ‘finish’ them, which can add a second firing in the kiln if the piece is glazed. The irony is that I got hooked on using clay due to its immediacy, however, the process soon becomes time-consuming once the drying time and firings are taken into account.

Have you had to acquire new skills or develop new techniques in the process?

I think that when you take the plunge to translate tests and/or ideas into a fully-fledged piece of work, then there is loads of tweaking and new understanding as you go. The piece that is the riskiest (and therefore exciting) are the tiles that make up ‘Individual Motives’.

After firing I am taking the tiles to the studio of Martin Smith (acclaimed ceramic artist and former RCA Ceramics & Glass head of course), where we will trim them down using a diamond saw to achieve a crisp edge. I’ve never done that before, but need the tiles to ‘butt-up’ against each other in a precise way.

To achieve the scale that I want for ‘Flex’ I have had to do lots of work behind the scenes in preparation for the thick, heavy slabs. Time will tell if this works out. Other pieces that I am more practised at in the making are pushed in the installation (‘Create A Scene’ and ‘Fearful Symmetry’) or glazing stages (‘Panel Discussion’).

You're interested in shifting populations and the built environment – do you think a shift is happening now?

Shifting populations is always a prominent topic of conversation, and it is something we can all relate in one way or another. In the week of writing this, ‘President’ Trump has had his racist say on the international movement of people. Locally to me, East London has a rich and varied history of people arriving and leaving, and I love finding out more about this element of the area. This ebb and flow translate directly into aesthetic changes in the built environment, including its architecture.

Is now a good time to be based in London? How do you find it?

London is always fun and full of life. It has been my home for the past eight years, and I love living and working in Hackney. I am attracted to its transience in many ways, but it is also a shame that it prices so many people out of relaxing into staying here.

The demand (of which we are all part of) means greedy landlords can charge stupid rents comfortable in the knowledge that they don’t need you because you are a replaceable commodity. London is a game that I have enjoyed playing, but the more I know about its direction, the more I dislike it and think of moving on.