Meet the maker: Storyteller and model maker, Charles Young.

Charles Young is the imaginative, detail-driven architect behind the miniature paper metropolis, Paperholm.

Based in Edinburgh, his work is currently being exhibited at the Goethe-Institut, Glasgow - and we were lucky enough to check it out.

Beginning as a daily project, this carefully crafted and curated cityscape of cranes, concert halls, cars and churches quickly catapulted into a busy and bustling built environment.

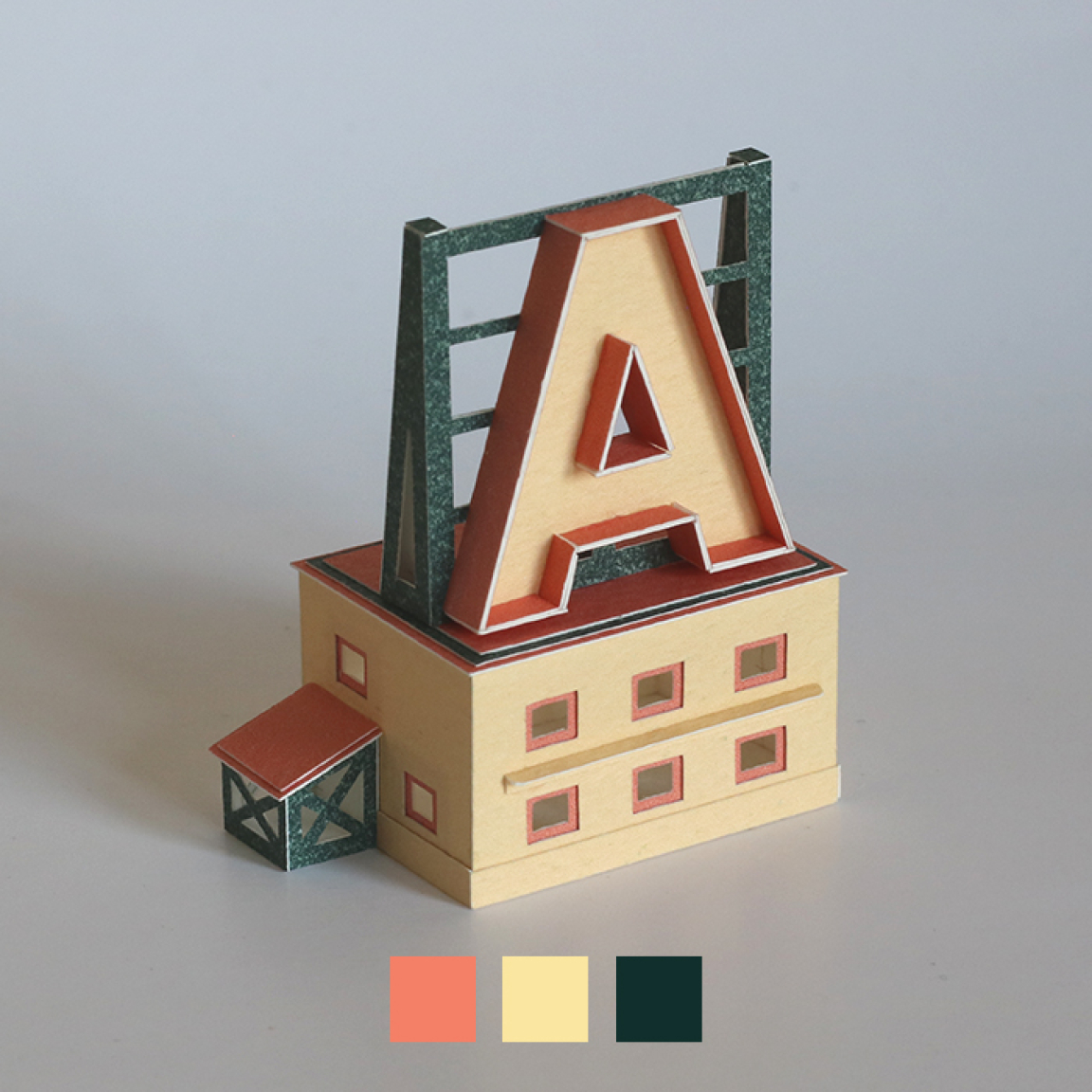

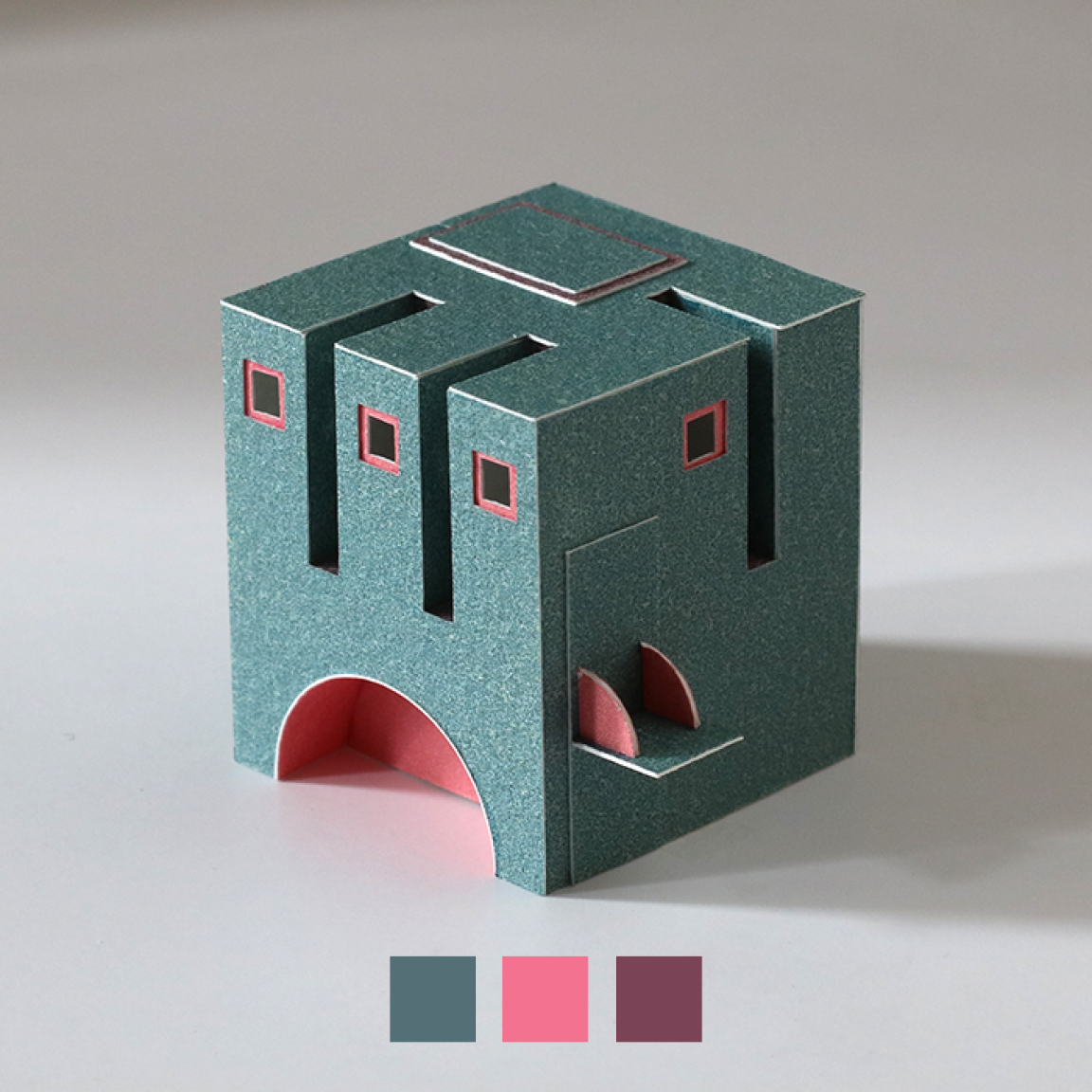

His practice takes a range of different forms, dipping into stop animation, photography and of course, model making, to capture the stories intertwined in our urban landscapes. Now introducing colour into his models as well, Charles adds a whimsical, Wes Anderson-like aesthetic to his hand crafted constructions.

Further expanding the materiality of his metropolises through carpentry, cane weaving and clay, we caught up with Charles to hear more about his making processes.

How did you get started?

“I’m based in Edinburgh and have been since coming here for art school in 2008. I started making artworks in paper after graduating from the Master of Architecture programme in 2014.

“I was looking for a project that would allow me to make something every day – the small paper structures really lend themselves to this, as the material is quick to work with and I could usually complete a piece in one sitting. From the starting point of these small paper sculptures, my work has expanded in scale over time to allow me to explore bigger ideas and stories.”

How do the technical and research skills you gained while studying architecture support your making process?

“Model making is a big part of architectural education, and the use of paper carries through from there. The pieces have become more complicated over the years and have a lot more detail than they used to at the beginning. You need to practise to improve your skills, and by making lots of small work, you get better.

“The ideas that I include in my larger sculptural work have their origins in the work that I was researching during my masters degree in Architecture. I was looking for stories of structures in the built environment that have become lost or displaced. Setting out architectural proposals requires research into what currently exists and what has existed on a site, so that you can ground your proposal in its context.

“I’m always looking for a compelling story to form the basis of a piece of work. Often the starting point for this will be looking at old maps of the city, then moving on to seeing what photographs and drawings are available in online archives.”

Can you please give us a glimpse into your making process?

“Making a piece of work in paper usually starts with a little sketch or just a rough idea in my head. The best of these pieces of work start with a strong idea of a shape, even if the details are improvised as I go along.

“I make these entirely by hand, so will start by drawing directly onto the paper and cutting out each individual piece with a scalpel. I place PVA along the edges of the paper so that I can use as little glue as possible, meaning it dries quickly and I can move on with construction straight away. I gradually build up the structure like this, as essentially a series of connected boxes, and add extra details to the surfaces.

“Making a larger piece of work will begin in the same way, with a paper maquette, but then progress to a final full scale structure of a wooden frame.”

How did colour come to be introduced to the Paperholm archive?

“When I started making the series of paper structures I was using just plain white watercolour paper. It meant that I only had to be concerned with the shape and form of the piece.

“In 2020 I found a book, first published in Japan in the 1930s and recently republished, of combinations of colours drawn from the art and design of that time. Sanzo Wada’s Dictionary of Colour Combinations includes hundreds of combinations of 2, 3 and 4 colours.

“I started working my way through the colour combinations in the book, printing a single A5 sheet of watercolour paper quartered with the four colours. This gave me a limited amount of material to work with, keeping the scale of each piece roughly the same, but offering an automatic way of introducing colour.”

How has material research and sourcing influenced your practice?

“When I first began to move away from the small paper models, and produce work on a larger scale, I was looking for a way to cut down on the amount of material that I was using so that I could make a light frame of wood and cover the surfaces using another method. Initially my idea was to use Shoji paper to cover the frames, linking back to the aesthetic of my earlier work, but I then picked up the idea of looking at other furniture-making techniques to look at how I could achieve a more robust surface that would still be translucent and not too solid.

“I settled on using rattan cane-weaving, a method most usually seen on chairs but also sometimes on larger pieces of furniture. You take soaked pieces of the cane, which are up to 4m long and weave them over your frame, through a series of holes around the edge of the open sections of the frame. I’ve also experimented with using other chair covering materials including ‘Danish’ cord, a material that is made from twisted brown paper, but looks like a long spool of string.

“The different materials can only be used in particular ways and this can constrain the way that you use them. The rattan cane-weaving can be used on any surface that you can drill holes into, whereas the ‘Danish’ cord is wrapped over the edge of the frame, determining more the shape and aesthetic of what you are making.”

Can you please tell us about your artist residency in Leipzig?

“From February until April this year, I took part in an artists’ residency at the Leipzig International Art Programme. The Goethe-Institut NORDIC Leipzig residency brings together artists from the nordic countries (and Scotland) to spend time developing new work at the Leipzig Baumwollspinnerei, a former cotton mill and current arts complex.

“Having a 100m² studio to live and work in made it possible for me to develop my ideas on a larger scale. I made investigative studies, using the different chair weaving techniques, building up to making a human sized sculptural structure. Having 5 other artists taking part in the residency at the same time made for a collegiate atmosphere where we could show what we were working on, and visit other places in Leipzig and Germany together to gather ideas.

“The focus of the large piece of work that I made during the final month of the residency was a former prominent Leipzig building, the Kuhturm. This tower, with it’s origins in a pre-medieval castle, became a watch tower in the middle ages before finally being demolished in 1939 to make way for an exhibition that never happened. I was able to find references in the form of drawings and photographs showing the tower in its original context, as well as its distinctive form of eight sides. I was inspired to try and recreate a new version of the tower with the idea of returning it to its original position.”

We're pleased to have caught your artist talk at the Goethe-Institut, Glasgow. What does it mean to currently be exhibiting there?

“It was great to be able to bring back the work that I made in Germany and show it in the exhibition in Glasgow. Putting together the show, as well as the artist talk, gave me the opportunity to reflect on the development process and to understand myself what it was that I had been doing.

“Sometimes it’s only in retrospect that you can see what it is that you have made and why. It’s also good to have to explain the work to other people as it can bring up ideas that you may not have realised were present.”

To learn more about Charles’ work, click here.